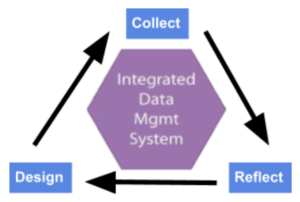

Teachers and students personalize data use by:

- Collecting useful data with students on their interests, learner characteristics, and academics;

- Engaging students in reflective, data-driven conversations where, together, they reflect on data; and

- Using insights from reflection to co-design and refine learning plans.

Teachers and students take ownership over data-use by collecting and using actionable data to design and refine personalized learning plans in regular, data-driven conversations with students called conferring.

Personalized learning involves students in making decisions over what, when, how, and where they learn. Teachers and students inform these decisions with the use of data. In collaboration with a team of researchers, I visited over a dozen schools over three years that are personalizing learning and spent a week or more in each of three schools carefully selected for their innovative data-use practices to learn from leaders, teachers, and students what data use looks like in cutting-edge classrooms.

1 – Collect

Create learner profiles and collect data on students, their interests, and their academic readiness.

We tend to think about student data in terms of compliance data, or data schools are required to collect such as scores on mandated state tests and attendance records but in the innovative classrooms I visited, teachers and students did not report this type of data being used.

In place of compliance data, teachers and students generated and collected new data on individual students, their interests, and their academic readiness. Students and teachers collect these data from various sources and typically store them in a document called the learner profile. Learner profiles are often Google Documents that both teachers and students have access to and are modified regularly. I found that teachers and students collect and use data that fall into two categories – data on students as individuals and data on student progress through academic standards.

Data on Individual Students

Teachers and students aggregate and store data on students as learners from: self-assessments on their learning styles, intelligences, and mindset; student reflections on their learning preferences and ideal learning environment; teacher observations of students and their readiness for independent learning; and how students have developed over time.

Teachers and students also collect and store information on student interests and goals in the learner profile. Students reflect on and document their interests in and out of school such as their hobbies, things they want to learn more about, activities they would like to try, and possible career paths. While most of this information comes from student reflection, students’ career goals are often influenced by digital career guidance tools.

Data on Academic Readiness

Teachers and students both share responsibility for maintaining an up-to-date accounting of standards- and proficiency-based academic progress. Students and teacher often collect student progress data from digital learning programs. However, no school we visited relies on student progress in digital learning platforms alone as an indicator of student proficiency. Students and teachers also collect and store benchmark assessment data from tools such as NWEA MAP or Renaissance STAR. Together these data let students, teachers, and parents know where the student is in regards to learning standards.

2 – Reflect

Create time to regularly reflect on data by conferring with students.

Teachers and school leaders in the schools we visited build into their master schedules time for regular, one-to-one, data-driven, conversations between a student and a teacher—a process known as ‘conferring’. During these conversations, teachers scaffolded a student’s capacity to set learning targets, craft learning pathways, and design meaningful assessments or evidence of learning through modeling, thinking aloud, guided questioning, and by giving students opportunities to take control of the conversation.

Conferring provides time for teachers to build relationships with students, to check in with them and learn about their lives and interests in and out of school. Students reflect on their academic progress and relate progress to decisions and actions taken during time for independent learning.

Where does the time come from? Teachers create time for conferring by scaffolding student capacity and scheduling independent learning time. Starting off, teachers work to train students, establish routines, and set expectations for student-directed learning time. Teachers also make time by establishing workshop / station-rotation routines, effectively grouping students, engaging in team teaching, and incorporating learning technologies—to name a few. With one or more of these strategies in place, student learning continues in the classroom even when the teacher is not directly engaged in group instruction, and the teacher has created time to confer with individual students.

3 – Design

Create opportunities for students to choose their own learning targets, make learning designs, and decide how they will show evidence of learning.

After reflecting on available data, conferring conversations shift into co-designing student learning pathways and assessments. Teachers and students work together to form a plan that aligns—when possible—student interests with learning activities while making progress through learning standards.

In some programs, students start with control over these conversations, with teachers backfilling support as needed. In others, teachers gradually release control over to students. Regardless, teachers tell me that they observe regular conferring and time to practice self-regulated learning resulting in increased student capacity for independent learning.

How to get started

The needs and interests of our students are always changing, as is the context in which learning takes place. This renders personalizing learning an inherently iterative design process. Teachers in the schools I visited are constantly reflecting on data, collecting evidence, and thinking about what was is working, what is missing, and what needs to change. If you are just getting started, pick one or more data elements that you find compelling and engage one or more colleagues in a design session with the goal of integrating your chosen element into your daily practice. Regardless of what element you choose, the three steps should be present: collect, reflect, and design.

Give it a try and share your experiences with us. What data do you collect? How do you use it? Does this article match your experience? I’d love to hear from you.

[This blog post was originally authored for the Institute for Personalized Learning.]

About the Author

Alan Barnicle is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Education and Director of the Personalization in Practice Research Group. His research interests focus on practice and include designing for learning, data information systems, education leadership, and socio-technical systems for learning.

Twitter: @abarnicle

Email: abarnicle@wisc.edu