What we measure and pay attention to matters.

What we measure and pay attention to matters.

What we measure and pay attention to matters. I argue that how we use this information matters more. For better or worse, student data has become the currency of schooling. Teachers exchange grades and scores – proxies for learning – for student’s effort and performance. Moreover, at school and system levels, educators trade student performance on standardized tests, recognition, reward, and censure. At all levels, academic exchanges are in place to reduce the friction of moving between student scores on tests and literal material benefits and liabilities through college admissions and employment (e.g. professional advancement, student scholarships, and college admissions).

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and New Measures of School Quality

Now, with the passage of ESSA school systems have a new opportunity to identify and report indicators of school success not directly related to student performance on state exams (U.S.C., 2015). But what might these measures be? Several states, for example, are considering measures of student social and emotional learning (SEC, e.g. Minnesota, Wisconsin). Whatever we choose, it will be important to collect and use this information in a way that does not create perverse incentives to game the system (I’m thinking of ‘bubble kids‘ under NCLB) to achieve ‘better’ results without creating better conditions for learning.

How data is used matters more.

Like currency, generating student data is all too often seen as a school-system goal, an end. Unfortunately, educators have traditionally collected and used information more to sort students than to advance individual student learning. Recently, teachers differentiating instruction and providing tiered supports have taken a more student-centered approach towards data use. Investigations on data-use in schools have focused on how teachers and school leaders use standards-based assessments to inform decisions at the school or system level; with little effect on improving classroom instruction. Results from these studies are often discouraging; teachers do not tend to find representations of these data timely or actionable and often lack time and routines to make sense of data and use it to change instructional practices (L. Hamilton et al., 2009; Little, 2012; J. a. Marsh, Farrell, & Bertrand, 2016).

Moving towards student-involved data use

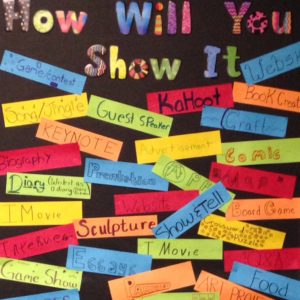

Some have focused attention on how effective school systems design formative feedback systems to inform and improve instruction (Halverson, 2010). Even these models were developed before personalized learning took off and did not investigate what data-use looks like when students are involved. Although there have been a few who have investigated student involved data use (SIDU), these studies have focused on discussing interim assessment outcomes with students and setting related goals for growth. For more on SIDU see Jimerson, J. B., Cho, V., & Wayman, J. C. (2016). Student-involved data use: Teacher practices and considerations for professional learning.). Personalized learning schools take a comprehensive approach towards the collaborative collection and use of data in the instructional design process.

New designs for learning reveal new orientations towards school data.

New designs for learning are likely to yield new practices. To date, researchers have not given much attention to how teachers and students are collecting data in personalized learning classrooms, or how they collect and use data for standards- and interest-centered learning aims. I’ve written a bit on how some schools are including students in the information use process and am currently wrapping up a study to fill this gap in the literature.